Teaching History as it Happens

Contextualizing three Wednesdays in January.

April 2021

As a teacher of ancient history in sixth grade and early American history in seventh grade, I jump at the opportunity to bring current events into the classroom. Bridging the gap between events that occurred hundreds, and at times thousands, of years ago with stories that our students see in the world around them is part of what makes History such a dynamic subject.

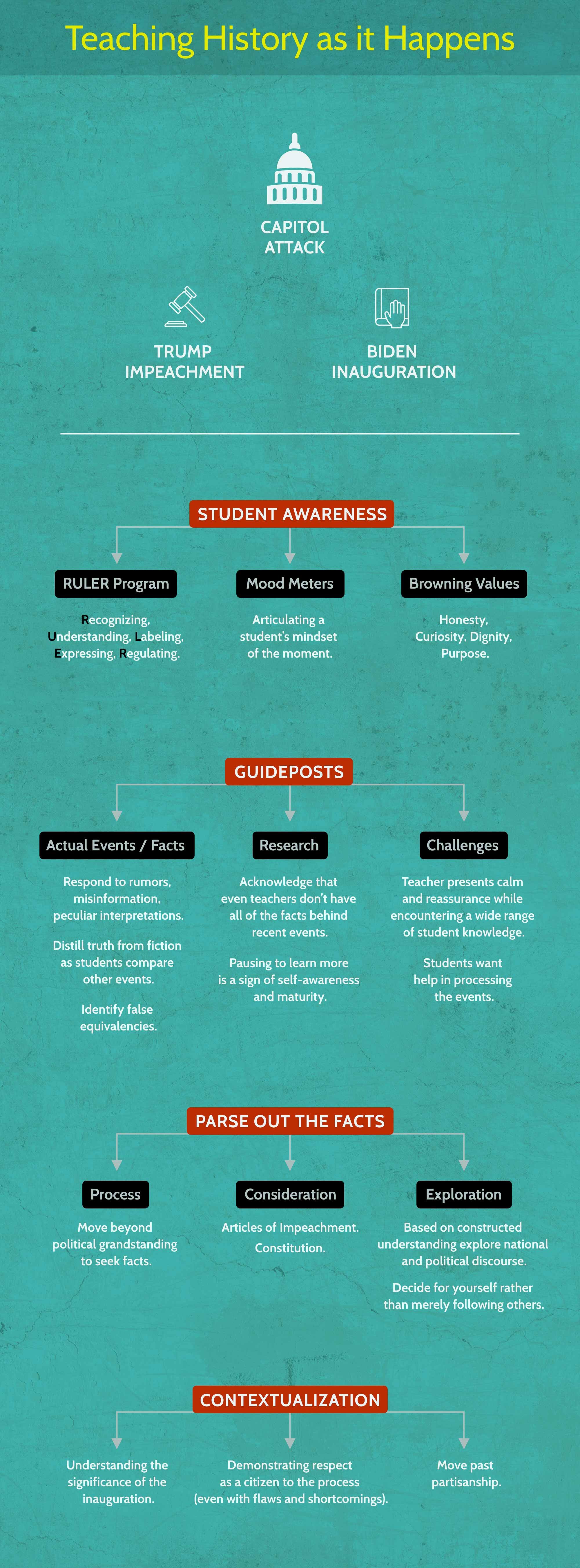

With that opportunity comes responsibility. No clearer was that responsibility than when the attack on the Capitol unfolded on Wednesday, January 6. In fact, there were several monumental Wednesdays in January: the attack, the second impeachment of President Trump, and the inauguration of President Biden.

With many members of our community tired from the toll of 2020, turning the page on that calendar year and looking ahead to 2021 took an added eagerness. For some, the end of 2020 marked the remembrance of many Americans who have lost their lives to COVID-19 and the disruption the pandemic had on all of our lives. For others, the end of the year marked a literal turning of the page and a determined focus to look ahead. Either way, the start of 2021 had an additional weight and sense of importance. In reality, for many of us it was a combination of the two, among other things, that occupied our thoughts for the first few days in January.

We were quickly reminded that viruses do not pay attention to calendars and while many things do start anew in a new year, not all is forgotten. On January 6, many Americans were captivated by images of the Capitol being attacked and taken over. The breach and attack as well as the response (or lack thereof) of government officials raised important questions that are difficult for anyone to answer. For Middle School students, ensuring their awareness of these major events, as well as providing space for discussion and questions, is important.

In my classes, awareness of these events varies wildly, so my first step in class the following day is to check in with my students. Incorporating the school’s use of the RULER program and the Mood Meter, students are able to articulate their mindset in the moment. From there, we can have a broader conversation about what happened, how it affects them, and what may or may not happen next.

There are two guideposts that I find helpful for such conversations: reliance on factual accounts of an incident as well as leaning on community values: reminding ourselves of the Browning’s commitment to honesty, curiosity, dignity and purpose. These guideposts provide a foundation from which classrooms can develop open conversations that explore questions of what is happening in the world around us while simultaneously making meaningful connections to their studies and their lives.

With these guideposts, it is easier to respond to the inevitable: a rumor you had not heard, misinformation, a peculiar interpretation or connection that may not totally be based in fact. These moments are challenging, as teachers strive to balance space for students to express themselves with an obligation to present the facts. And, even with the plethora of reporting on an event such as an attack on the Capitol, the social media live-streams and real-time tweeting, it can still be hard for even the most savvy consumer to distill truth from fiction. As a result, I am willing to acknowledge when I lack information and need to do research. Not only is it the truth, but it also models for the boys the ability that we all have limits to our own knowledge, especially around current events, and pausing to learn more is not only acceptable but a sign of self-awareness and maturity.

Acknowledging these limits does not preclude a teacher’s responsibility to correct false information or false equivalencies. Frequently, during these conversations students attempt to make connections or comparisons to other events and ideas. Making connections should be applauded, and misguided equivalencies should be identified as such. In the context of the insurrection, there is a temptation to compare it to the protests over the past year in particular around Black Lives Matter. Unpacking this comparison thoughtfully is both important and possible: First, what motivates the two groups; what is their claim? Insurrectionists argue that the 2020 Presidential election was stolen and, therefore, the process as outlined by the Constitution should not proceed. Black Lives Matter demonstrators call for police to stop killing Black people. Second, what recourse is available to these groups? For those opposing the 2020 election, options included recounts and legal challenges. Opponents of the election results, as well as former President Trump’s campaign pursued these challenges rigorously and extensively, and they were unsuccessful. For Black Lives Matter demonstrators, when confronted with violence, a natural instinct is to call the police. In fact, that is what many Americans are taught. However, what if the source of the violence is the police? Citizens are not able to start criminal proceedings on their own, and police officers are afforded broad civil protection under the law. Therefore, their recourse is limited.

Once we start to explore these motivations and available recourse, we see that these two public events are not as similar as we may have originally thought. It is important to understand that students will often bring outside information to such a conversation, and trying to strip away the political rhetoric is valuable. Of course, that is easier said than done.

Yet, there are times when our boys expect us, as teachers, to have all of the answers, so lifting the curtain can invoke anxiety. Simultaneously, it is important for any teacher to present a certain measure of calm and reassurance, even in the absence of having all of the answers. Knowing all of this, it can, therefore, be surprising how some middle school students respond. They range for naivety and ignorance to “where did you read that?” incredulity. Sprinkled within that range, one might also find indifference or curiosity.

During the first impeachment of former President Trump, one student bravely asked, “I’m a Democrat. What am I supposed to think?” Although he asked with a slight smile, recognizing, on some level, that the question is a bit silly, he also had a genuine desire for help in processing these events. After some groans from the Trump supporters in the room, I answered the question with how, not what, any Democrat, Republican, or unaffiliated person should approach this topic: the first step is to parse out the facts. In a process that is so rife with political ramifications, grandstanding and accusations, even that process can be challenging. From there, consider the Articles of Impeachment and the underlying facts. Unfortunately, the standard established by the Constitution is not much help. Is impeachment warranted? Finally, based on that constructed understanding, one can explore the national / political discourse and see with whom one agrees. So, as I explained to the student, figure out what you believe first and then find who agrees with you. Don’t look to people you tend to agree with and then construct your understanding accordingly.

Despite the insurrection and subsequent impeachment of former President Trump, on Wednesday, January 20, Joe Biden was inaugurated as President. That week, our Middle School students were learning remotely, so various teachers hosted a live viewing of the event via Zoom. I hosted one such viewing open to all of my students. A group of students, as well as some faculty, joined to watch one of the hallmarks of American democracy: the (traditionally) peaceful transition of power. Although former President Trump broke with many customs by refusing to acknowledge the results of the election or to attend the inauguration, at noon on Wednesday, January 20, President Biden began his term.

Understandably, the event looked different than previous inaugurations, with the overall scale reduced on account of COVID. Nevertheless, the significance of the moment of the moment was clear as, even before we gathered to watch, some boys interrupted class to share that the event had begun. We celebrate the inauguration of a new president not as partisan supporters of a particular president but as citizens demonstrating respect for the political process, even while recognizing its flaws and short-comings. It’s not an either/or proposition. One can admire a process while simultaneously trying to improve it. After all, isn’t that what teaching is all about?