In the Fight Against Polarization, Libraries Lead the Way

Discussions help boys build critical thinking skills

May 2024

School libraries are places where students can nurture their love of learning, learn research skills, or simply use some free time to curl up with a good book. But in a world where questionable “news” has become ubiquitous, and where social media thrives on misinformation, the library at the Browning School has an important role to play in exposing students to new cultures and experiences, helping them understand the rationale behind opinions they already hold, and creating a safe space for them to question, explore and learn. In an age where adults appear to be increasingly polarized, the skills learned in our library are ever more important for our boys to learn.

Library Director Murielle Louis (she/her) says the library's goal is to "enhance students' communication skills, encourage meaningful conversations across diverse perspectives, and cultivate a harmonious and inclusive community.” As an example, the fifth graders in her media literacy class learn to think more deeply about the information they are ingesting by studying memes and commercials. “We've talked about stereotypes in memes—for example, distorted facial features on African-Americans. I want to know what they understand and what they can see in those images.”

She adds that when a student used stereotypical images in an assignment he created, she led a class discussion about it. “I was surprised when one of the students said that it was a microaggression. It shows that students themselves can identify these things, and they have the language to do so.”

Lower School Librarian Samantha Gill teaches students 'PIE' (persuade, inform, entertain) book evaluation.

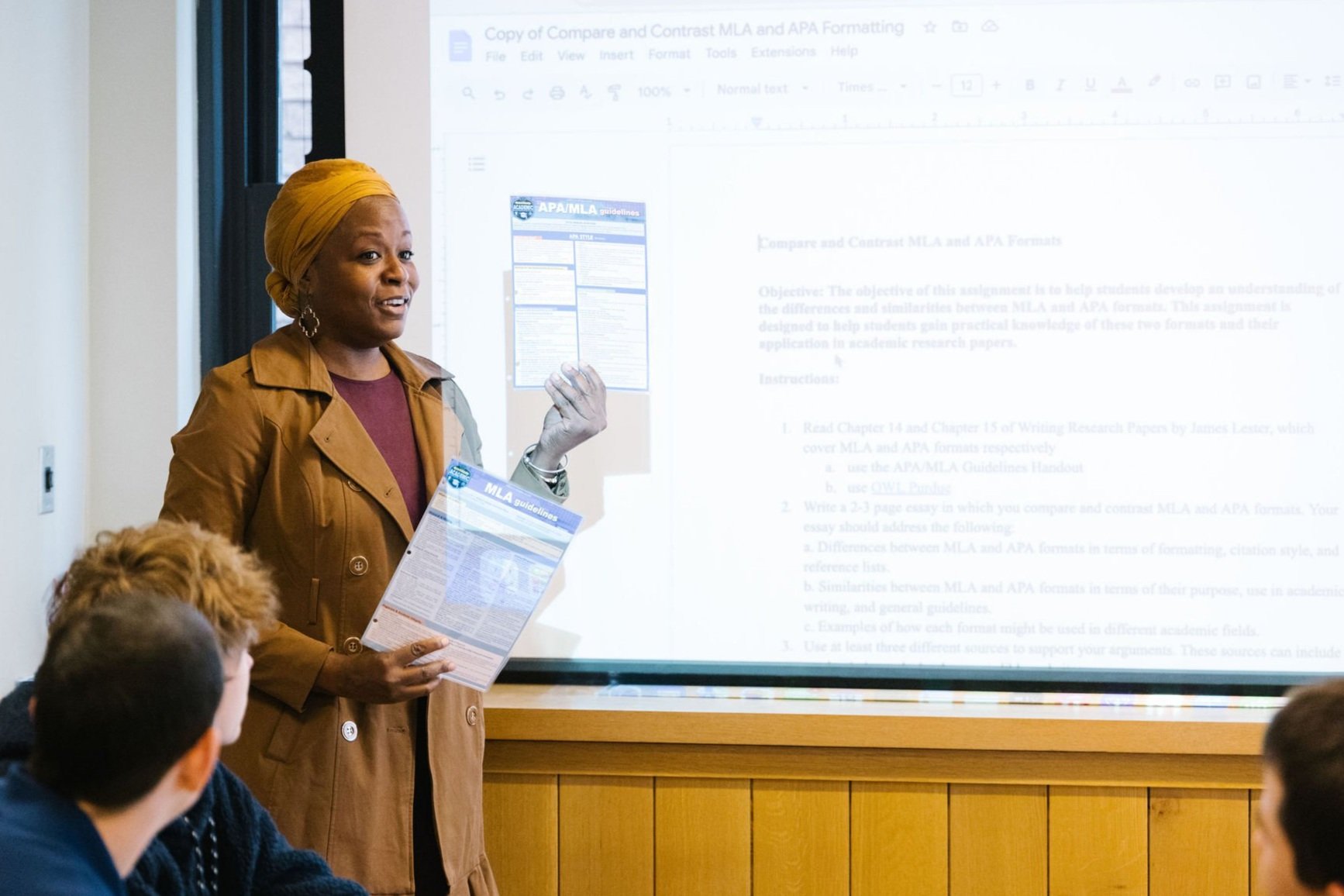

Library Director Murielle Louis teaches about citations for research projects.

While the youngest students have different interests, they too have many opinions and can be taught how to express them respectfully. Samantha Gill, (she/they), the Lower School librarian says, “My goal from kindergarten all the way to fourth grade is to make them recognize why they have these opinions, not to tell them what opinion to have.”

Ms. Gill starts every class with a “would you rather?” ice breaker question and gives students a few rules. One is that everyone gets to state an opinion that isn't based on degrading the other choice. “Many kids will immediately go towards expressing a negative opinion of the other option, which is something that we see societally in adults as well. It's a way of protecting and validating their opinion.”

Ms. Louis, who teaches media literacy to Grades 5 and 6, and works with older students on a variety of research projects, says that explaining how to judge the validity of sources is crucial. This is particularly true in middle school when students begin working with a Chromebook. “Suddenly all this information is being thrown at them and who do they trust? Learning what constitutes accurate information is a big topic, even for adults,” she says.

Ms. Gill is teaching that active discernment as early as Grade 1. “We discuss how authors and illustrators are making intentional choices and that we may not always know the reason that they made those choices. I let them know it's okay not to have the answer to everything, but to also question the intention behind things.”

When teaching students how to evaluate books, Ms. Gill uses the acronym 'PIE' (persuade, inform, entertain) so that students can understand the author's purpose in telling a story. These are then concepts that Ms. Louis' students are already familiar with as they look at memes, articles or television commercials. And it can help them think about how and when people are seeking to influence their opinions.

“I encourage them to actually hear the other side of an argument,” Ms. Louis says. “Having a strong opinion about something doesn't mean you shouldn't listen to the other side respectfully. Our intent is never to change their minds, because children obviously bring their values from home to us. But at the Browning School, we listen to everyone, and we don't shy away from different sides of difficult topics.”

Ms. Gill wants to make sure that our younger learners recognize all of the choices that they are making, and why they are making them. She tells them, "Let's expose the reasons you believe the things that you do, so that you can explain yourself to other people." She adds, "We also make sure that they understand nuance, so that they can move beyond black-and-white thinking. When they get to fourth grade, you need to be able to really articulate your opinion.”

Younger students also read the books that are nominated for major awards such as the Caldecott, and decide whether they should be honored. "Not only are they thinking about what and how the books are teaching them, but also about whether they liked learning from the book,” she says.

“I try to make the intuitive visible, forcing them to recognize the things that their brains are actually doing very quickly," Ms. Gill says. “Polarization sometimes comes from a knee jerk reaction—you know that you feel a certain way, but haven't done the analysis to back it up.”

The library is also a place where students will be exposed to displays and information about various commemorations such as Women's History Month or Black History Month. “Occasionally a student might ask why we don't have a Men's History Month, and that can open up an important discussion,” Ms. Louis says.

What is most important is that the library at Browning is a safe space for all kinds of opinions expressed respectfully. As Ms. Gill says, “Kids feel like they have a little bit more of that agency here and that they aren't going to just get shut down. Asking questions here is always okay, as long as you're asking for information or clarification and it's on topic. We are here to answer.”